17 Chapter 23: First Aid Provider

Welcome! Tansi!

Essentials of Firefighting

Course Objectives

- Describe the role of the fire service in providing emergency medical care. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Explain patient confidentiality requirements. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Identify communicable diseases that first responders commonly encounter. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Explain ways to prevent the spread of communicable diseases during emergency medical care. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Explain the process of patient assessment. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Describe Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Describe methods of controlling bleeding. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

- Explain shock management. [6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.2.1]

To accomplish the mission of the fire service, it is your responsibility as a firefighter to save lives. Nowhere in the fire service is this responsibility more relevant than in the delivery of medical services. The fire service provides emergency medical care in many ways, and you must become familiar with the way your department provides medical care. You must also be proficient in the medical skills and duties assigned to function effectively as a firefighter.

NFPA 1001, Chapter 6 establishes guidelines for emergency medical services (EMS) training in jurisdictions. The chapter states that the AHJ is responsible for training firefighters to one of the five levels:

- First Aid Provider

- Emergency Medical Responder

- Emergency Medical Technician

- Advanced Medical Technician

- Paramedic

Certification to levels 2-5 are at the discretion of the AHJ and are governed by standards and requirements outside the scope of this course. Level 1, First Aid Responder, describes EMS capabilities that all firefighters should know and serves as a minimum standard of EMS training in all jurisdictions.

These capabilities include:

- Infection control

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- Bleeding control

- Shock management

The information contained in this chapter is intended to satisfy the entrance requirements for firefighter training in NFPA 1001. However, it is not a substitute for formal training as an emergency medical care provider. The chapter begins with an introduction to fire service-based emergency medical care and important laws regarding patient confidentiality. It continues with information about infection control practices, patient assessment, and CPR, and concludes with content on bleeding control and shock management.

Now, what?

Let’s get learning!

Lesson 1

Outcomes:

- Describe the role of the fire service in providing emergency medical care.

Fire-Service-Based Emergency Medical Care

Emergency medical services (EMS) is commonly known as the treatment on scene and the transport of victims to a healthcare facility. While the fire service has a long tradition in the United States, EMS has only had formal recognition since the 1960s. However, the fire service has been a key provider of emergency medical care since its inception.

Fire departments provide EMS in a number of ways. Even if the organization does not operate ambulance units, its personnel often serve as medical first responders to provide treatment until an ambulance arrives.

Ambulance services are typically provided in one of the following ways:

- Fire-based EMS: Ambulance service is provided as a function of the fire department.

- Staffing is typically provided by firefighters who have been cross-trained as emergency medical technicians (EMTs) or paramedics.

- In some jurisdictions, the fire department sometimes provides ambulance service, but EMTs and paramedics who do not have firefighting responsibilities provide staffing.

- Third-service EMS: An organization separate from the fire and police services, which has its own administration and personnel that provides ambulance service.

- In most instances, this organization is a function of a municipal, county, provincial or regional government.

- In some jurisdictions, a for-profit or not-for-profit organization that is under contract may provide service.

- Hospital-based EMS: Ambulance service is contracted to a hospital by the local government.

- Personnel work at the hospital and patients are typically transported to the contracted hospital for treatment.

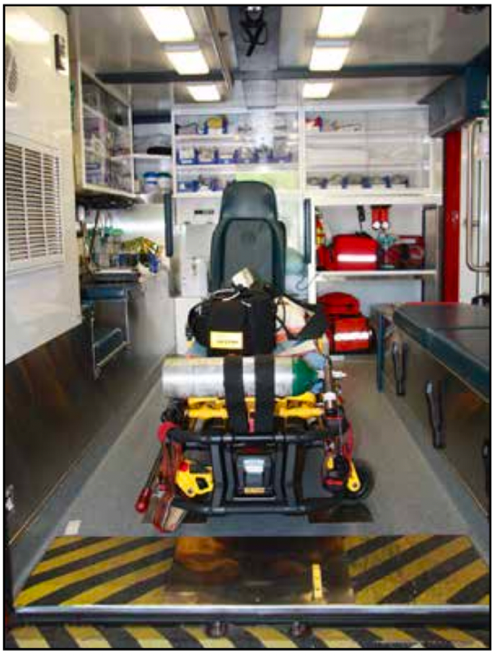

Regardless of the type of ambulance service provided in your jurisdiction, become familiar with the equipment, protocols, and standards of care used (Figure 23.1). In areas where the fire department does not provide ambulance service,

it is especially important that firefighters train regularly with EMS personnel and that the units have a good working relationship.

In many jurisdictions, fire department personnel can respond to an emergency medical call faster than EMS units. In most areas, there are multiple fire stations and apparatus, but few ambulances. In addition, some areas routinely have more medical calls than available ambulances. For these and other reasons, fire departments are often requested to respond to the scene and begin care until EMS personnel arrive.

Some departments provide this service with personnel who have limited EMS training, while others provide fully functioning paramedics who carry most of the same equipment and medications on the fire apparatus that are carried on an ambulance (Figure 23.2). Regardless of the level of service that a department provides, you will likely be called upon to provide some type of emergency medical care.

Test Your Knowledge!

Lesson 2

Outcomes:

- Explain patient confidentiality requirements.

Patient Confidentiality

Healthcare providers must safeguard the protected medical information (PMI) of a patient. In Canada, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) has been instituted at the federal level and regulates the use, distribution, and storage of PMI. The law also establishes civil and criminal penalties for noncompliance. Provincially, each province may enforce additional regulations on the use, distribution, and storage of PMI.

The equivalent of the PIPEDA in the United States is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, which federally regulates the use, distribution, and storage of PMI.

Fire departments are typically required to follow these regulations if they provide medical care and bill electronically for services. PIPEDA regulations dictate how and to whom PMI can be shared and how the information is to be protected from unauthorized disclosure.

If your department is bound by PIPEDA regulations, the department will have a designated privacy officer who will handle the proper storage distribution and use of PMI. With the support of senior management, the designated privacy officer will advocate the department’s privacy management system in compliance with PIPEDA.

Regardless of your department’s obligations under PIPEDA, it is good professional practice to be discreet with PMI. This means that PMI should only be disclosed to those with a legitimate need. Individuals who often require this information include law enforcement personnel, EMS personnel, and hospital staff (Figure 23.3). Release of PMI to others can only be done with the consent of the patient. As someone expected to provide medical care, you should become familiar with and adhere to guidelines that the department and AHJ establish.

Lesson 3

Outcomes:

- Identify communicable diseases that first responders commonly encounter.

Infection Control

As a firefighter, you may be called on to provide medical care to patients with communicable diseases. Communicable diseases are not always obvious; the ability to identify signs and symptoms of common communicable diseases along with the use of proper body substance isolation (BSI) procedures will greatly reduce your risk of infection. Immunizations are also an important safeguard against infection.

Commonly Encountered Communicable Diseases

Firefighters can be exposed to people with communicable diseases. Some diseases that are regularly encountered include hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) such as staph infections. Several types of influenza may also be encountered.

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver. Viral hepatitis is most common, but drugs, alcohol, hazardous chemicals, or heredity can also cause the disease. Symptoms include a viral-like illness with yellowish discoloration of the eyes and skin.

The different types of viral hepatitis are:

- Hepatitis A: Typically caused by consuming food or water that has been contaminated, particularly by fecal matter. Hepatitis A can be transmitted by close contact with infected individuals. Signs and symptoms of hepatitis A include: fatigue, abdominal pain, fever, dark urine, and a marked yellowing of the skin and/or eyes. This typically has no long-term consequences to an individual. Hepatitis A is the least serious form of viral hepatitis.

- Hepatitis B: Typically transmitted through blood and other body fluids. Hepatitis B infections can be short-term or long-term in nature and can cause serious scarring and injury to the liver. It can progress to liver failure. Signs and symptoms of Hepatitis B resemble those of Hepatitis A. Hepatitis B is a serious and potentially lifelong infection.

- Hepatitis C: Typically transmitted through blood and other bodily fluids. Hepatitis C differs from other types of hepatitis because infected individuals can go for many years without exhibiting symptoms. While the individual feels fine and is symptom-free, the virus has probably done serious damage to the liver. In some cases, this damage can be long-term or permanent. Liver failure can occur as with hepatitis B.

- Hepatitis D (Delta): This uncommon strain of hepatitis only occurs in individuals who are also infected by Hepatitis B. This virus makes the effects of Hepatitis B much worse.

Vaccines are available for hepatitis A and B, but those for hepatitis C remain in development. Firefighters need to be immunized against hepatitis and other infectious diseases. The best way to combat hepatitis is by thoroughly washing your hands and maintaining proper BSI procedures which will be detailed later in this chapter (Figure 23.4).

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection that primarily affects the respiratory system. TB is contagious and airborne. It spreads when infected persons breathe, cough, or sneeze. Because of how the disease is transmitted, incidences of TB are more prevalent in high-density living areas such as nursing homes and prisons (Figure 23.5).

TB is considered to be active when the infected individual exhibits signs and symptoms of the illness. Signs and symptoms of active TB include:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Chills

- Weight loss

Figure 23.5 Tuberculosis is spread via airborne droplets and is prevalent in nursing homes and other places with dense populations. Courtesy of Ron Moore, McKinney (TX) FD. - Painful breathing

- Productive cough (often with traces of blood)

- Coughing that lasts several weeks

Because the signs and symptoms of TB are often similar to other illnesses, take BSI precautions and use an N-95 mask, even if your patient is not known to be infected. (N-95 masks are detailed later in this chapter). No widely used vaccine protects against TB, but healthcare providers are typically skin-tested annually to check for exposure to the disease.

In addition, an annual purified protein derivative (PPD) test may be administered to determine exposure to tuberculosis. This test is performed by injecting an inactive bacterium just under the skin. You will be required to return to have the results determined within 48-72 hours. A reaction to this test may indicate that you have been exposed to tuberculosis. In these instances, a chest x-ray and follow-up with a physician may be necessary to determine if there is an active infection. However, there are occasionally individuals whose result is a false-positive.

HIV/AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a result of prolonged exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This condition weakens the affected person’s immune system to the point where the body is unable to fight off diseases that a person with an uncompromised immune system could overcome. Early symptoms are similar to other viral illnesses, but more advanced stages of the disease lead to severe muscle wasting and an increased likelihood of contracting other infections. Due to this weakened immune defence, many persons with HIV are likely to have diseases such as hepatitis and TB. HIV is spread through contact with infected blood and bodily fluids. While HIV/ AIDS are serious diseases, they pose far less risk to emergency responders than hepatitis and TB due largely to the short amount of time that HIV can survive outside of a body. However, it remains important to practice proper BSI procedures and to decontaminate any medical equipment before it is used on another patient. Information on the cleaning and disposal of contaminated items is provided later on in this chapter.

Multi-Drug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs)

Multi-drug-resistant organisms are an increasing concern in healthcare settings because they are difficult to control and do not typically respond to conventional antibiotic treatment. Drug-resistant staph infections, also known as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are commonly encountered types of MDRO. MRSA infections typically occur in healthcare settings, but there have been outbreaks in communities. These infections can develop in numerous ways but are usually initially seen as abscesses in the skin that are commonly mistaken for spider bites. Because MRSA infections spread easily, proper BSI precautions must be taken. In addition, all reusable medical equipment such as stethoscopes, blood pressure cuffs, and backboards must be sanitized after each use to prevent these types of infections from spreading.

Other Diseases

Occasionally there are outbreaks of infectious diseases that occur in communities. Recent outbreaks in North America include H1N1 influenza (swine flu), avian influenza (bird flu) and others. Different infectious disease outbreaks could occur during your time as a firefighter. Regardless of the disease, emergency responders should be prepared to treat affected patients. Proper sanitation and BSI procedures will go a long way toward keeping you and your patients safe.

Tests and Treatment for Communicable Diseases

If you are exposed or possibly exposed to a communicable disease, you will follow local SOPs to be tested or treated for a variety of possible exposures. Some diseases, such as TB, may have annual testing procedures in place in your jurisdiction. In other cases, if patients test positive for a communicable disease like HIV, you may be treated immediately for the disease and then tested later to see if you contracted the disease or if treatment was successful. Other jurisdictions may test you whenever there is a possibility of exposure and compare these tests against baselines.

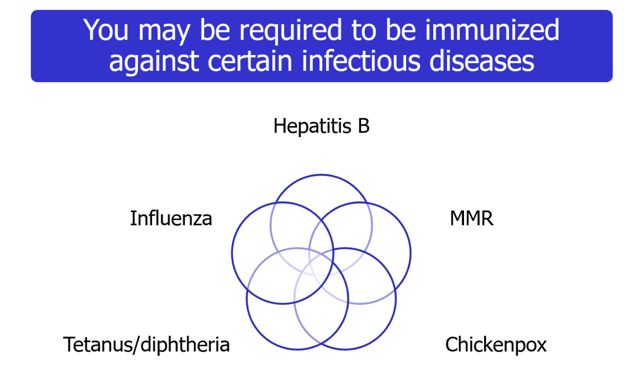

Immunizations

As an emergency responder, a jurisdiction may require you to be immunized against certain infectious diseases if you have not already done so (Figure 23.6). Immunizations that may be required or recommended include:

- Hepatitis B

- Varicella (chickenpox)

- Influenza

- Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR)

- Tetanus/diphtheria

Body Substance Isolation (BSI)

Diseases are spread by pathogens, organisms that carry the disease and can cause infection. Pathogens exist in the body fluids of infected persons and can be transmitted from one person to another through contact with these fluids. While any type of body fluid can carry pathogens, blood-borne pathogens are encountered most often. Airborne pathogens are also a threat.

Exposure occurs when the body fluid of an infected individual comes in contact with an exposed area of another person. There are numerous routes where emergency responders are susceptible to exposure. These include open wounds, cuts, and sores on the body. Other routes of exposure include contact with the eyes, nose, or mouth. Any break in the skin is a potential route of exposure (Figure 23.7).

With the threat of exposure to communicable diseases, it is critical that firefighters take all precautions necessary to protect themselves from exposure. The best way to do this is by maintaining proper BSI procedures. BSI is an all-encompassing group of procedures that include hand washing, proper use of personal protective equipment, and proper disposal and/or cleaning of soiled items. The Canadian provincial health authorities and the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) serve as good sources of information for establishing BSI procedures.

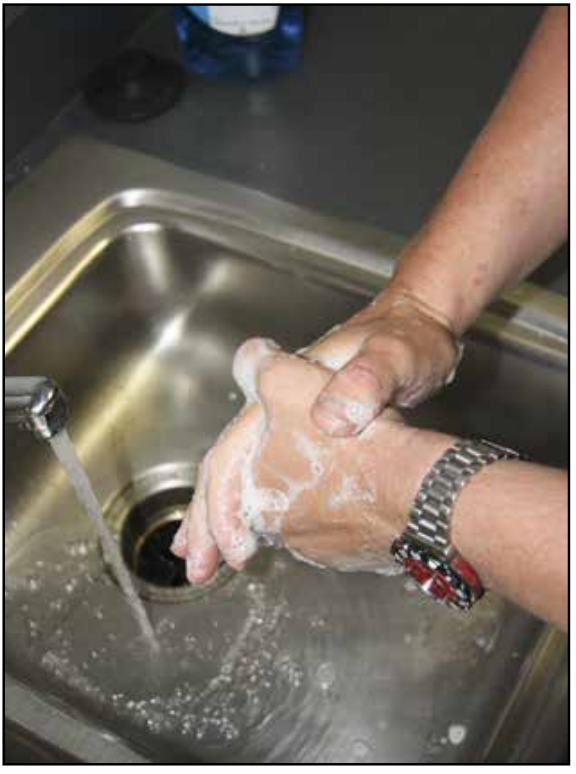

Hand Washing

Proper hand washing greatly reduces the transmission of disease and should be done frequently. This is especially true before and after coming in contact with a patient. Hands should be washed methodically with warm water and soap (Figure 23.8). Special attention should be paid to soiled areas, the areas between fingers, and fingernails. In addition, it is good practice to wash the wrists and forearms. A specially designed scrub pad may also be used. Hands should be washed for at least 30 seconds to ensure thorough cleaning.

Hand washing is often not possible when responding to emergency calls. In these cases, an alcohol-based hand-cleaning solution should be used (Figure 23.9). This is especially true after providing patient care. It is a good practice to clean your hands with an alcohol solution before entering the passenger compartment of the apparatus.

Test Your knowledge!

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

To prevent the transmission of infectious diseases, emergency responders must use adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). PPE allows emergency responders to adjust their level of protection based on the potential threat of infection (Figure 23.10). In some instances, this may mean simply wearing gloves. In other cases, a gown, mask, eye protection, and gloves may be needed. A jurisdiction will dictate the level of PPE that should be worn on emergency medical calls. When selecting PPE, it is better to wear too much than not enough. Refer to your department’s SOPs regarding PPE use on emergency medical responses. These sections discuss types of PPE in more detail.

Gloves

Gloves are an essential component of PPE and should always be worn during patient contact. In the past, medical gloves were typically made from latex. Unfortunately, some patients and healthcare providers have an allergic reaction to this material. Many jurisdictions supply emergency responders with gloves made from vinyl or other material. If your jurisdiction uses latex gloves, it is important to ask the patient if he or she has a latex allergy. Non-latex gloves should be available in these instances.

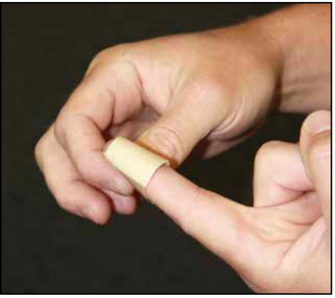

Removing Gloves

When moving from one patient to another, remove the old gloves and don a clean pair before providing treatment. Many responders carry multiple pairs of gloves for these instances. To remove soiled gloves, place two clean fingers on the inside of the glove and peel off (Figure 23.11).

Soiled Gloves

Gloves soiled with blood or other body fluids should be disposed of in a sealed container that is specifically used for the disposal of biohazards. These containers are typically red in colour and have a red liner (Figure 23.12).

Eye protection

Because the eyes are a route for disease entry, eye protection is necessary when blood or other body fluids can be splashed, sprayed, or spattered. Safety glasses are a commonly used during medical responses (Figure 23.13).

Safety Glasses

Safety glasses keep fluids away from the eyes and usually provide some type of impact resistance. Accessories are available for those who wear prescription glasses so they can be modified for use. In addition, emergency response agencies often use a combination mask and eye shield (Figure 23.14). Helmet shields and Bourke Eye Shields do not provide suitable eye protection for emergency medical use.

Masks

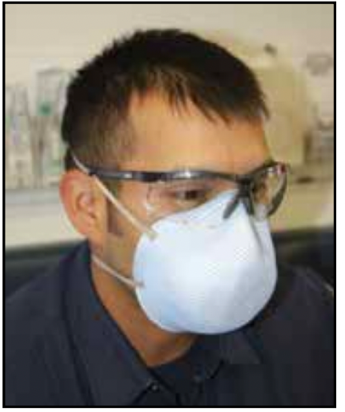

Masks protect against respiratory hazards, airborne pathogens, and body fluids. In situations where contact with blood or other body fluids are a concern, surgical-style masks typically suffice. However, if you suspect that a patient has a communicable respiratory disease such as TB, it is best to use a mask that provides a greater level of respiratory protection.

In these instances, placing a mask on the patient can also prevent the transmission of the disease to others.

N-95 Respirators.

When treating patients with TB, the jurisdiction may provide N-95 respirators. These respirators are termed N-95 because they are tested and shown to block at least 95 percent of airborne particles (Figure 23.15). Because a proper seal is necessary to provide protection, prospective wearers should be fit-tested to ensure that they can obtain a complete seal with the respirator and that they are able to perform required activities while wearing it.

Gowns

Gowns protect exposed skin and your uniform from the spray and spatter of body fluids. They are especially useful in situations such as trauma and emergency childbirth. As with all PPE, know where gowns are stored on the apparatus or ambulance and be able to don a gown quickly (Figure 23.16).

Spare Uniforms

A department may require that you have an extra uniform ensemble available at the station or on the apparatus in case your clothing becomes soiled (Figure 23.17). Not only does a soiled uniform look unprofessional, but it can also allow for the spread of disease. Follow departmental guidelines regarding the cleaning of soiled uniforms. In case of extreme contamination, immediately shower and notify the department’s infection control officer.

Cleaning and Disposal of Contaminated Items

Medical equipment and non-disposable PPE that come into contact with any patient must be considered to be contaminated. Decontamination must follow the requirements of NFPA 1581, Standard on Fire Department Infection Control Program, and the department’s infection control protocol.

Follow these general steps for decontaminating equipment and PPE:

- Wear disposable gloves, mask, and eye protection to place contaminated items in a biohazard bag or container.

- Transport the contaminated items to the designated disinfecting area of the fire station or other facility.

- Don the appropriate splash-resistive eyewear, cleaning gloves, and fluid-resistant clothing designated for de-contaminating equipment.

- Use a solution of bleach and water or disinfectant in accordance with the equipment or PPE manufacturer’s instructions (Figure 23.18)

- Do not decontaminate equipment or PPE in the kitchen, bathroom, or other living areas of the fire station.

- Contaminated station uniforms or structural PPE must not be taken home or cleaned in normal laundry facilities (Figure 23.19)

- Decontaminate the sink and cleaning area, remove PPE worn during cleaning, and dispose of in accordance with fire department protocol.

Contaminated disposable equipment and PPE must be placed in medical waste containers and disposed of in accordance with local protocol. Needles and blades must be placed in sharps containers designated for such items. Sharps containers must be closable, puncture-proof, leakproof, and labeled according to federal, state, or local regulations.

Lesson 4

Outcomes:

- Explain the process of patient assessment.

Patient Assessment

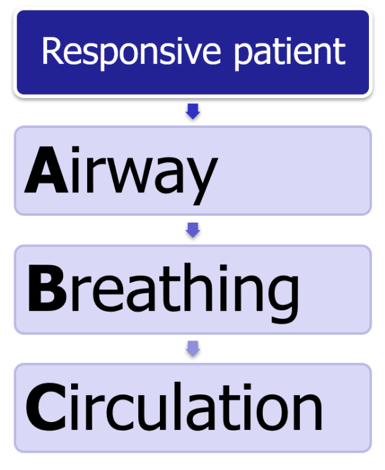

Before medical treatment can begin, the patient’s condition must be assessed. The most basic assessment is to determine whether critical functions of the body work properly. If the patient is responsive, the assessment involves an evaluation of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, which has traditionally been known as the ABCs. Most of the patients cared for by firefighters will be responsive and assessed in this manner.

Before medical treatment can begin, the patient’s condition must be assessed. The most basic assessment is to determine whether critical functions of the body work properly. If the patient is responsive, the assessment involves an evaluation of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, which has traditionally been known as the ABCs. Most of the patients cared for by firefighters will be responsive and assessed in this manner.

Agonal Respirations = Irregular gasping breaths.

In patients that are unresponsive and not breathing or breathing with irregular gasping breaths (also known as agonal respirations), the assessment sequence should be rearranged to Circulation, Airway, then Breathing (CAB). For patients who are not breathing, starting high-quality chest compressions as soon as possible increases the patient’s chances of survival.

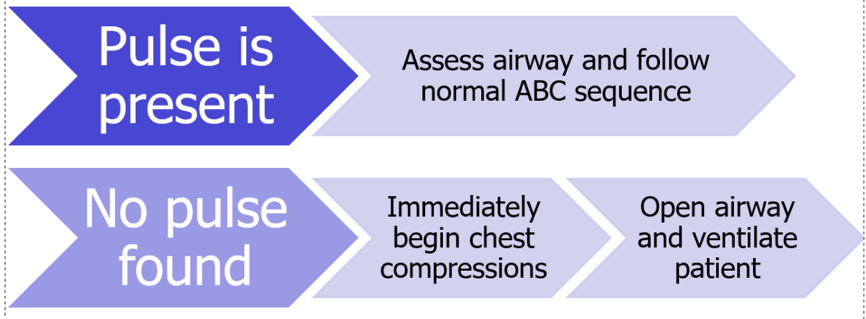

If a pulse is present (as is usually the case), then assess the airway and follow the normal ABC sequence. If no pulse is found, immediately begin a cycle of chest compressions and then open the airway and ventilate the patient: the cardiac arrest CAB sequence. The following sections identify the ABCs of patient assessment in greater detail. Remember that formal CPR training will provide more definitive information on the performance of assessment techniques.

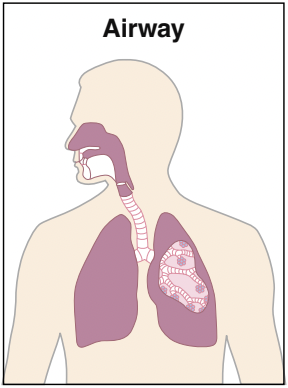

Airway

A patient’s airway is the passage between the lungs and the nose and mouth where air travels during breathing (Figure 23.20). If the tongue, a foreign object, or fluid obstructs the airway, air cannot travel freely. If the patient is able to talk and appears to be breathing without difficulty, it can be assumed that the airway is clear. However, if the patient is unresponsive, an airway may need to be opened. Techniques for opening the airway are introduced during formal CPR training.

Breathing After determining that the airway is open, assess whether the patient is breathing. Place your ear near the patient’s nose to listen for sounds of breathing. You should be able to hear the patient breathing through the mouth or nose. Look at the mouth and the chest to see if the patient’s chest is rising and falling (Figure 23.21). When feeling, exhaled air can be felt. If the patient is not breathing or no air moves during breathing; provide assistance. Techniques for rescue breathing are introduced during formal CPR training.

Circulation/Compressions

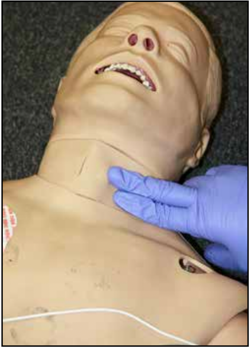

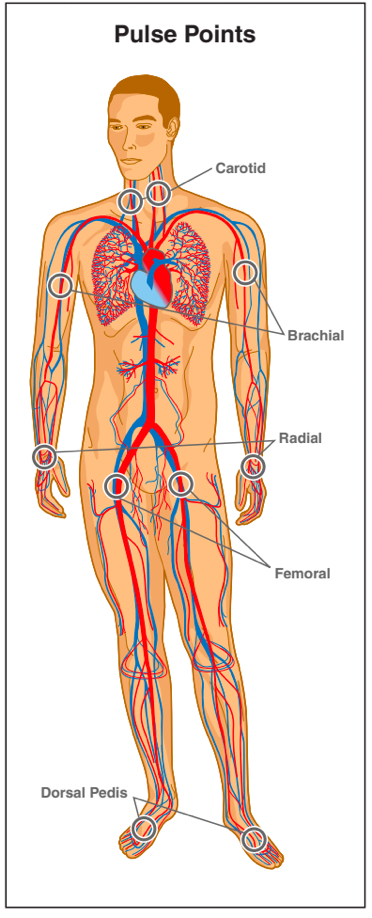

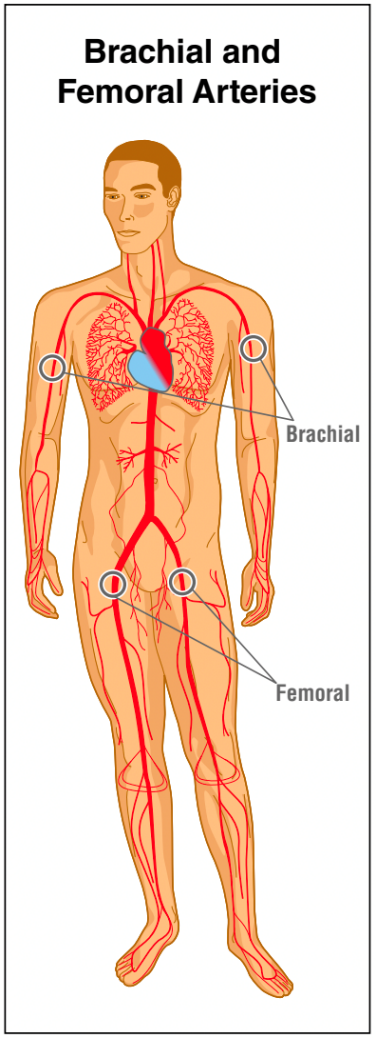

Circulation/compressions is the flow of blood through the body. The easiest way to determine the presence of circulation is to feel for a pulse (Figure 23.22). Common locations to find a pulse are shown in Figure 23.23. Most pulses get assessed at the radial and carotid arteries for adults and brachial arteries for infants. Because of the distance of the radial artery from the heart, it typically takes stronger blood flow for a pulse to be felt in this area than at the carotid artery. Therefore, just because a pulse cannot be found at the radial artery does not mean that the patient is pulseless. In these instances, attempt to find a pulse at the carotid artery as well. If a pulse cannot be found, chest compressions should be initiated immediately.

Test Your Knowledge!

Lesson 5

Outcomes:

- Describe Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Clinically dead: When the patient’s heart stops beating and is no longer breathing.

Cardiac arrest: When the heart fails to circulate blood through the body, and the cells are not able to receive the oxygen and nutrients needed for survival.

Biological death: Continued cell death to the point where organs such as the brain, heart, and lungs get irreversibly damaged and cannot be revived.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): The act of physically forcing blood through a patient’s body and providing artificial respiration.

Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

Cardiac Arrest

A patient is considered clinically dead when his or her heart stops beating and is no longer breathing. During this condition, known as cardiac arrest, the heart fails to circulate blood through the body, and cells are not able to receive the oxygen and nutrients they need to survive. In the span of a few minutes, these cells begin to die. If this condition is allowed to continue for much longer, cell death will progress to the point where organs such as the brain, heart, and lungs get irreversibly damaged and cannot be revived. This is known as biological death, and at that point no amount or type of medical intervention can revive the patient.

The heart produces electrical impulses that cause it to contract and force blood throughout the body. Heart failure that causes clinical death is in many instances the result of a problem with the heart’s ability to produce and/or transmit these impulses. This condition often persists unless an outside electrical stimulus is applied. This outside stimulus is commonly known as defibrillation (Figure 23.24).

Advanced-level EMS providers are trained to recognize electrical issues with the heart and manually administer defibrillation and medications that treat these issues. Unfortunately, several minutes could pass for these personnel to arrive on scene. During this time, the patient may have gone from clinical death to biological death.

In some instances, the heart’s condition may not warrant defibrillation. In others, defibrillation may not resume the heart’s function. In this case outside intervention is needed in order to circulate blood through the body and slow the rate of cellular death.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the act of physically forcing blood through a patient’s body and providing artificial respiration. The following sections will highlight how to perform layperson CPR on adults, infants, and children. Layperson CPR gets performed differently than CPR for healthcare providers.

In particular, a higher priority gets placed on chest compressions than patient assessment. Keep in mind that this information is provided to satisfy entry requirements for NFPA 1001 and does not take the place of a formal CPR training program. If you are to provide this care, you need to become certified in CPR from your department, the American Heart Association (AHA), and/or Canadian Red Cross. The AHA and Red Cross are considered the standard for CPR training and protocols.

Automated External Defibrillators

Realizing the importance of early defibrillation, many public facilities such as shopping malls, schools, and airports have automated external defibrillators (AEDs) available for layperson use (Figure 23.25). These devices instruct the layperson on how to use the AED, automatically determine if defibrillation is needed, and notify the user to push a button that delivers the shock. It is also common to find AEDs on fire apparatus that do not carry paramedics and their equipment. If you have an AED available, use it as soon as necessary. All AEDs come with instructions for use. Follow the unit’s prompts and instructions and note the results. If the AED is unsuccessful, you should then proceed to manual CPR described in the remaining sections below.

Chest Compressions

The main component of CPR is chest compression, which is the act of forcefully compressing the heart in order to circulate blood throughout the body (Figure 23.26). Patient survivability during a cardiac arrest improves with early administration of chest compressions. When performed properly, chest compressions compress the heart between the patient’s sternum and spine in rapid succession and alter the pressure within the chest, forcing blood from the heart. Chest compressions are performed in different ways and at different rates and depths, depending on the age of the patient.

**Note: If at any time during CPR an AED becomes available, interrupt chest compressions to attach the AED. The AED will analyze the patient. After analysis, follow the prompts from the AED.**

Administering Chest Compressions

Events of cardiac arrest are extremely stressful for all persons involved because the event is typically unexpected. When arriving at the scene of a cardiac arrest, CPR may or may not already be in progress. Your first priority after donning appropriate PPE is to determine the condition of the patient.

While CPR is a lifesaving intervention, it should not be administered to those who have signs of irreversible death. If there are no obvious signs, better-trained personnel should make determinations about the death of a victim.

Signs of irreversible death may include:

- Rigor mortis

- Obvious wounds not compatible with life (such as decapitation)

- Decomposition

The techniques identified in this chapter are for layperson CPR. As such, there is a greater emphasis on providing chest compressions than providing ventilation. Therefore, rescue breathing will not be addressed in this chapter. The American Heart Association provides reviewed and endorsed research that shows compression-only CPR is extremely effective and still provides some air movement into and out of the lungs. Full CPR incorporates chest compressions and rescue breathing.

Most emergency responders are certified in CPR to the Basic Life Support (BLS) for Healthcare Providers Level. It is critical that you attend and obtain certification from a formal CPR training course provided through your jurisdiction, the American Red Cross, or the American Heart Association. The following sections will detail chest compression administration for adults, children, and infants.

Chest Compressions for Adults

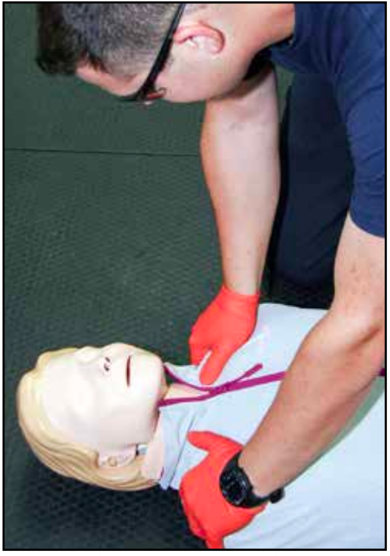

Upon arrival for a suspected cardiac arrest, it is critical to identify the patient and determine the patient’s status. The first determination should be the patient’s consciousness. Gently shaking or tapping the patient and asking them for a verbal response can determine consciousness (Figure 23.27). If there is no physical or verbal response, determine if the patient has a pulse. If no pulse can be found at the carotid arteries within 10 seconds, chest compressions should be started. The communications centre should be notified of the condition and any additional resources needed.When performing chest compressions on an adult, the patient must first be lying on their back on a hard surface. A patient who is lying on a bed should be moved to the floor; performing chest compressions on someone lying on a soft surface is typically ineffective. Next, find the correct location to administer compressions.

This location is in the centre of the patient’s chest between the nipples (Figure 23.28).

To perform compressions, place one hand on top of the other and complete the following steps:

- With the victim on his or her back, tilt the victim’s head back to open his or her airway.

- Straighten arms and lock elbows. Elbows should remain locked while performing compressions.

- Align your shoulders directly over your hands. This ensures that compressions are delivered straight down (Figure 23.29).

- Press straight down on the chest hard enough to depress the sternum 2

to 2.5 inches (50 to 60 mm) but no farther. While it may be difficult to judge the depth of compression, compressing to a greater depth may potentially harm the patient (Figure 23.30).

-

Figure 23.30 The sternum should be depressed at least 2 inches (50 mm). Lift up to release the compression. The chest should recoil completely when you lift up to allow the heart to fill itself. However, keep your elbows locked at all times and do not remove the hands from the compression location.

Chest compressions should be administered quickly and firmly at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. Responders should rotate the performance of chest compressions as needed to prevent exhaustion (Figure 23.31). Compressions should be continued until the patient moves, begins breathing normally, regains consciousness or until responders with greater training arrive.

Chest compressions should be performed in a firm, rhythmic manner. It should never feel as though you are jabbing at the patient.

** NOTE: While performing chest compressions, it is often common to hear or feel a patient’s ribs break due to the pressure. While this sensation is not pleasant, it is a sign of quality compressions and should not discourage you from continuing. **

Chest Compressions for Children

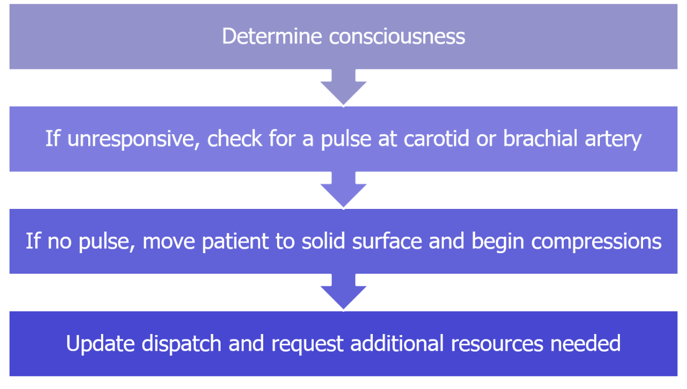

When arriving on scene for a cardiac arrest involving a child, first determine the patient’s status. Gently shake or tap the child to determine if conscious. Speak to the child and listen for a response. If the patient is unresponsive, check for a pulse at the carotid or brachial artery. If no pulse can be found, begin chest compressions.

You should move the patient to the floor or onto a backboard if the patient is not lying on a solid surface. This would be a good time for you or another responder to update dispatch with the condition and request any additional resources that may be needed.

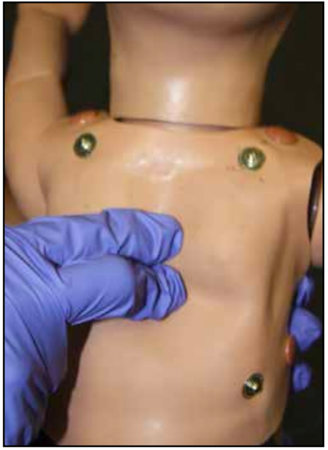

Chest compressions are performed on children ages 1 to about 12 in a slightly different manner than on adults. For larger children, rescuers can use two hands for chest compression as they would for an adult. For smaller children, rescuers should only use one hand to avoid injuring the victim (Figure 23.32).

On small children, the rescuers hand should be placed in the centre of the chest in line with the patient’s nipples. When performing compressions, the patient’s chest should be compressed about one-third of the depth between the chest and the back or about 2 inches (50 mm). This ensures that adequate blood flow is achieved. Compressions should be administered firmly at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. Continue administering compressions until the child begins to move, regains consciousness, breathes normally or rescuers with more complete training arrive.

Chest Compressions for Infants When responding to a cardiac arrest in an infant patient (less than one year old), first determine the patient’s status. Most incidences of cardiac arrest in infants are due to airway obstructions. If an obstruction can be seen in the mouth, remove it (Figure 23.33). If not, gently shake or tap the child to determine if he or she is conscious, looking for movement or other response.

If there is no response, check for a pulse at the brachial artery. If no pulse can be found (check 10 seconds), begin chest compressions. While beginning compressions, have another responder update dispatch on the patient’s status and request any additional necessary resources.

Chest Compressions for Infants

Chest compressions for infants are performed with the index and middle fingers of one hand (Figure 23.34). This allows the chest to be better compressed than with the heel of the hand. As with adults and children, the compressions should be delivered in the center of the chest in line with the patient’s nipples.

Compressions should be delivered at a rate of at 100-120 compressions per minute, and the infant’s chest should be compressed to one-third the depth of the torso, about 1.5 inches (38 mm). Periodically check the patient’s mouth to see if any obstructions are present. If so, remove them from the infant’s mouth and reassess.

Discontinuing CPR

Periodically reassess the patient during CPR to determine if the procedure is working. The main way to determine whether CPR is successful is if the patient regains consciousness or begins to move. Another way is to periodically check for a pulse. If the patient regains consciousness, begins to move, or has a pulse, CPR should be discontinued and the patient should be transported to a definitive care facility.

Once CPR is initiated, it should continue until one of the following events occurs:

- The patient begins to move and/or regains consciousness

- The patient has a pulse

- The patient breathes

- You hand over care to a rescuer with a higher level of training

- A medical control physician instructs you to stop

As a rescuer, you must understand the emotional nature of cardiac arrest events. This is especially true if the patient’s family or friends are present. When deciding not to begin CPR or when discontinuing CPR without patient response, you may be subject to anger or other emotional responses from bystanders. Speak calmly to family and friends of the deceased and to keep in mind their feelings when discussing the patient with other emergency responders.

Lesson 6

Outcomes:

- Describe methods of controlling bleeding.

Bleeding Control

Blood transports oxygen and nutrients to cells. Maintaining blood flow and volume is extremely important; therefore, emergency responders should be prepared to control bleeding in victims. There are two types of bleeding: external and internal. This section will describe the types of bleeding as well as methods for bleeding control.

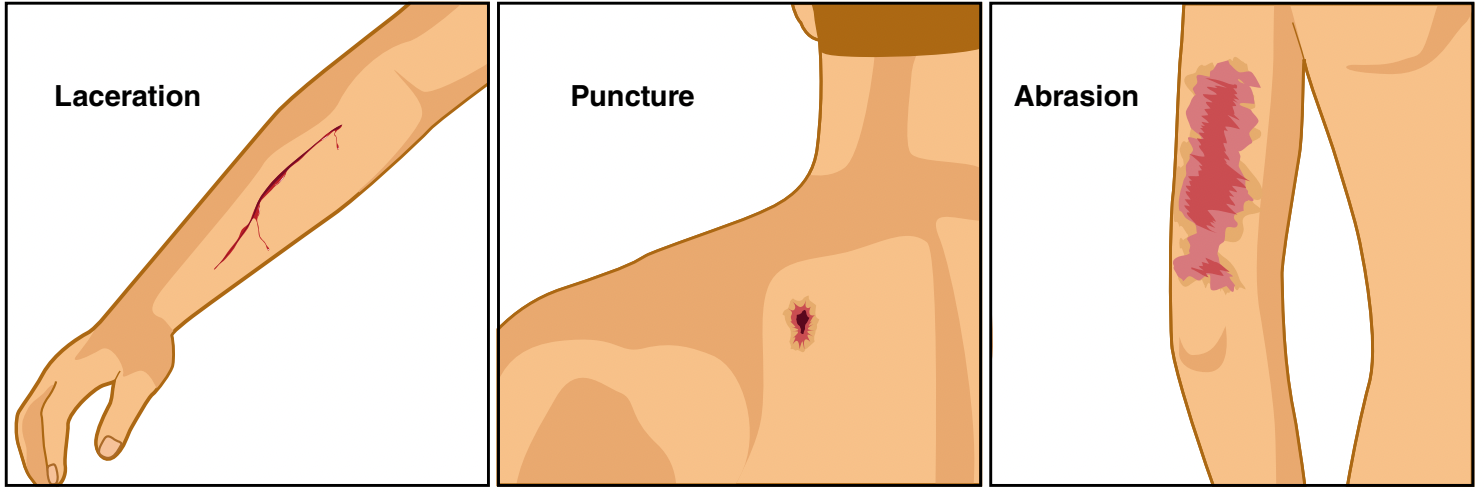

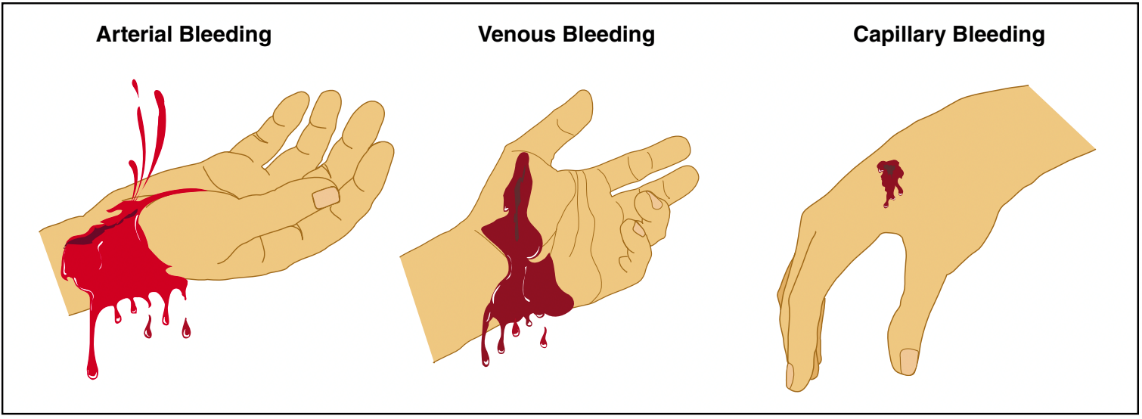

Types of External Bleeding

External bleeding is that which occurs outside of the body: lacerations, punctures, and other openings in the skin (Figure 23.35). There are three types of external bleeding: arterial, venous, and capillary.

Arterial Bleeding

Blood is transported away from the heart through vessels called arteries (Figure 23.36). The blood transported through arteries is under high pressure and is bright red in colour due to the large amount of oxygen it contains. Arterial bleeding occurs when the wall of the artery ruptures.

Arterial bleeding can be identified when the blood is bright red and spurting or pulsing (Figure 23.37). This spurting bleeding coincides with each contraction of the heart. As significant quantities of blood are lost, blood flow force decreases. Arterial bleeding is often difficult to control due to the substantial force of the blood and is a true medical emergency. Patients with arterial bleeding may lose a substantial amount of blood in a short time. Methods for controlling bleeding are discussed in this chapter.It is some-times not possible to stop arterial bleeding without surgery. Therefore, there should be no delay in transporting arterial bleeding victims to a hospital.

Venous Bleeding

Veins are responsible for returning blood back to the heart after it has delivered oxygen to cells. While arteries carry blood with substantial force, blood movement through veins occurs at a slow and steady flow. Therefore, venous bleeding is typically easier to control than arterial bleeding. Patients with venous bleeding will have a steady flow of blood. The venous blood will be much darker than arterial blood because oxygen has been removed by the cells and carbon dioxide and waste have been added.

Capillary Bleeding

Capillaries are the areas between arteries and veins where the oxygen and nutrients in blood are delivered to cells. In addition, carbon dioxide and waste are removed by blood through the capillaries. Because of this exchange, blood moves relatively slowly in capillaries. The majority of injuries to capillaries come in the form of scrapes or superficial lacerations.

When capillaries are injured, typically a limited quantity of blood oozes from the injury. Some capillary bleeding can stop without outside intervention. However, these injuries provide an opportunity for infection and should be properly cleaned and bandaged.

Arterial Bleeding: Characterized by bright red, spurting blood due to high pressure. It is difficult to control and is a medical emergency.

Venous Bleeding: Characterized by a steady flow of darker blood and is typically easier to control than arterial bleeding.

Capillary Bleeding: A slow ooze of blood from scrapes or superficial lacerations and can often stop without intervention — requires cleaning to prevent infection.

Lesson 7

Outcomes:

- Describe methods of controlling bleeding.

Controlling External Bleeding

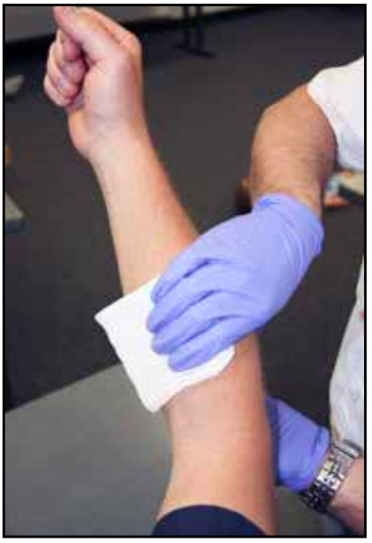

Methods to control bleeding include direct pressure and elevation. Depending on the type of bleeding, one or more of these methods may need to be used simultaneously. Always follow departmental medical protocols and recommended standards of patient care. Remember that proper PPE (gloves and eye protection at a minimum) must be used when treating patients with uncontrolled bleeding.

Trained medical providers use tourniquets to control bleeding. Tourniquets stop blood flow in large arteries above (closer to the heart) a bleeding wound to help stop blood loss. Their use lies beyond the scope of this chapter.

Direct Pressure

Direct pressure is the first and most commonly used method to control bleeding. Direct pressure can be applied with a gloved hand, a dressing or with a dressing and some type of bandage (Figures 22.38 a and b). With minor bleeding, the application of a dressing to the wound may be all that is necessary to stop the bleeding. If blood soaks through the dressing, more dressings should be applied on top in-stead of removing the soiled dressings. This procedure should continue until blood ceases to soak through. At this point, a bandage can be applied to hold the dressings in place and to keep pressure on the wound.

In more severe instances of bleeding, especially arterial bleeding, direct pressure should be applied with a gloved hand immediately. Blood can be lost so quickly in these instances that no time should be wasted in applying pressure. Once dressings and bandages are located and opened they can be applied to the wound.

Elevation

When injuries occur to extremities, elevation can be used in conjunction with direct pressure. Elevation is simply the act of raising the extremity above the level of the patient’s heart (Figure 23.39). Gravity helps to slow the blood traveling through the extremity, in turn slowing the bleeding. Elevating the extremity may not be possible in some instances, such as with fractures and injuries where spinal immobilization is needed.

Internal Bleeding

When blood vessels rupture inside the body, internal bleeding may occur. Internal bleeding is dangerous because spaces within the body can hold a considerable amount of blood before there is evidence of a problem. While this bleeding cannot be seen externally, there are several signs and symptoms that internal bleeding may be present.

These include:

- Significant bruising or other indications of injury, especially involving the patient’s torso

- Bleeding from openings such as the mouth, nose, or rectum

- Bloody stool or urine

- A painful, swollen, or rigid abdomen

- Vomiting of a substance that resembles coffee grounds

- Cool, pale, and clammy skin

Trauma and medical issues can cause internal bleeding. Traumatic causes of internal bleeding can include a gunshot or stab wound, motor vehicle accident, or fall. Medical causes of internal bleeding include ruptured blood vessels or organs.

Uncontrolled internal bleeding is a severe medical emergency. Patients with internal bleeding should be treated for shock. Patients who show signs and symptoms of internal bleeding should be immediately transported by ambulance to a hospital for treatment.

Lesson 8

Outcomes:

- Explain shock management

Shock Management

Shock is a condition that occurs when the body is unable to regulate itself and maintain normal function. In particular, a body in shock is unable to supply enough blood to vital organs to keep them functioning. This section will address the types of shock, the signs and symptoms of shock, and shock treatment.

Types of Shock

There are numerous types of shock. However, the most common types are hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and neurogenic. Both trauma and other medical emergencies can cause shock. Other causes of shock can be anaphylactic (due to allergic reaction) and septic (due to infection).

Hypovolemic Shock

When a patient loses a substantial amount of blood, he or she is at risk of suffering from hypovolemic shock. Shock occurs when the body is unable to supply blood to tissue. If there is significant blood loss as a result of internal and/or external bleeding, the body is unable to adequately supply the tissue. Therefore, hypovolemic shock is a “volume” issue because the amount of blood in the body is substantially reduced. The majority of instances of shock are due to hypovolemia.

Cardiogenic Shock

Even if the body has an adequate amount of blood, the heart still forces it through the body. Cardiogenic shock occurs when the heart is unable to force enough blood to tissue for it to continue functioning. This lack of supply is said to be a pump issue because the heart is unable to pump enough blood. A myocardial infarction (MI), more commonly known as a heart attack, is a main cause of heart impairment and can cause the body to quickly go into cardiogenic shock.

Neurogenic Shock

Blood vessels such as arteries expand and contract due to signals from the brain. Blood flow is carefully regulated in this manner. When blood vessels are expanded, significant amounts of blood can quickly travel through the body. Likewise, when blood vessels are constricted, very little blood is made available to organs and tissue. Neurogenic shock occurs when there is damage to the brain, spinal cord, or other nerves that control or regulate the blood vessels. This damage prevents the body from controlling the expansion and contraction of blood vessels as it normally would. Neurogenic shock is typically the result of the overexpansion of blood vessels. As the vessels expand, the pressure of the blood decreases due to the increased capacity. Therefore, neurogenic shock is said to be a “container” issue. Common causes for neurogenic shock are spinal trauma and head injuries.

Other Types of Shock

There are several other types of shock that can be encountered. One type is anaphylactic shock. Anaphylactic shock occurs due to a severe allergic reaction. Allergic reactions can be the result of issues such as food allergies, environmental allergies, and insect bites or stings.

Another type of shock is septic shock. Sepsis is the result of a severe infection in the body. While these types of shock are not as commonly encountered as the types listed earlier, they are still dangerous and should be treated as true medical emergencies.

Signs and Symptoms of Shock

Internal functions of the body such as pulse, blood pressure, and respiration are carefully adjusted to achieve optimal results. When a negative condition affects the body, it will adjust functions accordingly to maintain ideal results. However, if the condition continues, the body may not be able to maintain normal operations as it once did. Gradually, the body will begin to exhibit negative effects of the condition.

Signs and symptoms that someone is in shock or entering shock include:

- Pale/cool/moist skin

- Rapid heart rate (tachycardia)

- Rapid breathing (tachypnea)

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Confusion (also known as altered mental status)

- Others such as dizziness, dilated pupils, and loss of consciousness

Treatment for Shock

Because shock is a life-threatening condition, patients exhibiting signs and symptoms should be treated immediately and prepared for transport. Advanced life support treatments that paramedics provide are extremely important, however, those treatments should not delay transport to a hospital. Transport to a hospital can be viewed as a treatment and in most cases is the best treatment that can be provided to a shock victim. For this reason, transport of any patient exhibiting symptoms of shock should never be delayed. Place patients in a position to support blood flow to vital organs, such as lying on their back and feet elevated. Keep wounds or injuries elevated whenever possible. Oxygen should be used if within local protocols.

Using the methods detailed in this chapter, control bleeding immediately. A blanket should be used to cover the patient in order to maintain body temperature and prevent hypothermia (Figure 23.40). EMT intermediates and paramedics should be able to provide other advanced treatments for shock in these instances.