3 Chapter 2: Communications

Course Objectives

- Explain the procedures for receiving nonemergency calls. [NFPA 1001, 4.2.2]

- Describe the types of communications systems and equipment used to receive and process emergency calls. [NFPA 1001, 4.2.1]

- Explain the procedures for receiving and dispatching emergency calls. [NFPA 1001, 4.2.1]

- Describe radio equipment and procedures used for internal fire department communications. [NFPA 1001, 4.2.1, 4.2.2, 4.2.3]

- Handle emergency and nonemergency phone calls. [NFPA 1001, 4.2.1, 4.2.2]

- Use a portable radio for routine and emergency traffic. [NFPA 1001, 4.2.1, 4.2.3]

Now, what?

Let’s get learning.

Chapter 2: Communications

Fire department communications can be divided between emergency and nonemergency communications. Both can originate from the public, with emergencies reported directly or through 9-1-1 in most U.S. and Canada regions, or via standard phone numbers in some rural communities. Non-emergencies, like scheduling tours or fire code inquiries, are received on dedicated business lines. These communications are centrally processed and directed to relevant fire department units. Internally, however, emergency operations primarily involve radio transmissions. A firefighter’s effectiveness and safety depend on their knowledge of the local communication system and proficiency in using their assigned radio. Emergency calls might also be received on nonemergency lines or from in-person reports at the fire station, necessitating awareness of local protocols for such situations.

Lesson 1

Outcomes:

- Explain the procedures for receiving nonemergency calls.

Receiving Nonemergency Calls

Nonemergency calls received at fire departments include various inquiries, assistance requests, and personal calls. Each department has its own procedures for handling such calls, which should be known and followed. Always be professional and courteous when answering the phone.

On occasion, you may receive a call from someone who is angry or upset. When handling these types of calls you should:

- Remain calm and courteous.

- Never become confrontational.

- Be pleasant and take the necessary information.

- Refer the caller to the appropriate officer or division that can assist the caller.

In many departments, the Public Information Officer (PIO) is the contact person for nonemergency or complaint calls. You should become familiar with the functions and personnel in each division of your department so you can refer callers if needed.

Consider the behaviours below. Which ones would be appropriate for answering the non-emergency line?

- Answer calls promptly. (Correct)

- Identify only the department, omitting personal identification. (Incorrect)

- Be ready to record messages accurately, noting the date, time, caller’s name, phone number, message, and your name. (Correct)

- Leave callers on hold indefinitely if you’re busy. (Incorrect)

- Delay in posting or delivering messages, taking your time. (Incorrect)

- Avoid identifying the department, station or facility, unit, or yourself when answering. (Incorrect)

- If unable to answer a question, end the call without providing further assistance. (Incorrect)

- Promptly post or deliver messages to the intended recipient. (Correct)

- End calls courteously and disconnect according to local protocol. (Correct)

- Avoid leaving callers on hold for too long. (Correct)

- If unable to answer a question, refer the caller to someone who can, and follow up. (Correct)

Lesson 2

Outcomes:

- Describe the types of communications systems and equipment used to receive and process emergency calls.

- Explain the procedures for receiving and dispatching emergency calls.

Receiving Emergency Calls

The system for receiving emergency calls varies among communities, states/provinces, and regions regardless of the telephone number that is used. There are two broad categories of telecommunications systems:

- Emergency Service Specific Telecommunications Center — Separate telecommunications or dispatch centers that the fire department, emergency medical service, or law enforcement agency operates.

- Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) Central location that takes all emergency calls and routes the call to the fire, emergency medical, or law enforcement dispatcher.

Each communications centre should have specific equipment and procedures to properly manage emergency calls.

Public Alerting Systems

Enhanced 9-1-1 systems integrate telephone and computer technology, including computer-aided dispatch (CAD), to provide dispatchers with critical information such as the caller’s location, phone number, and directions to the site. Modern 9-1-1 services have expanded to include text messaging and smartphone applications.

Alternative Alerting Systems

Public alerting systems are those systems that anyone can use to report an emergency. Besides tele-phones, these systems include:

- Radio — An emergency may be reported by other public or private workers who carry radios. The same kind of information that would be taken from a telephone caller must be gathered.

- Wired telegraph circuit box — Historically, many cities installed street corner alarm boxes to allow citizens to report a fire. Pressing a leve

r on the box’s door transmits a unique code that identifies the location of the activated box. While reliable, they only transmit their locations not the nature of the emergency and are notorious for false alarms. Public telephones and cellular phones have diminished the need for these systems.

r on the box’s door transmits a unique code that identifies the location of the activated box. While reliable, they only transmit their locations not the nature of the emergency and are notorious for false alarms. Public telephones and cellular phones have diminished the need for these systems. - Telephone fire alarm box — Telephone fire alarm or call boxes are equipped with a telephone for direct voice contact with the telecommunications centre.

- Radio fire alarm box — A radio fire alarm box contains an independent radio transmitter powered by a battery, small solar panel, or spring-wound alternative.

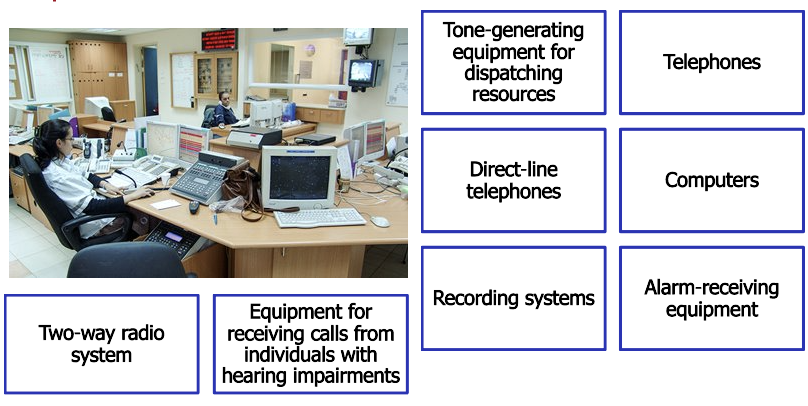

Communications Centre Equipment

Depending on local requirements and capabilities, telecommunications centres (Figure 2.1) contain a variety of equipment required for handling emergency calls. Some common pieces of communication equipment include the following:

- Two-way radio system for communicating with mobile and portable radios at the emergency scene as well as base station radios in fire stations or other department facilities

- Telecommunications Device for the Deaf (TDD), Teletype (TTY), and Text phone for receiving calls from individuals with hearing impairments.

- Tone-generating equipment for dispatching resources

- Telephones for receiving both emergency and nonemergency calls

- Direct-line telephones for communications with fire department facilities, hospitals, utilities, and other response agencies

- Computers for dispatch information and communications

- Recording systems or devices to record telephone calls and radio transmissions

- Alarm-receiving equipment for municipal alarm box systems and private fire alarm reporting systems

Figure 2.2 An example of the variety of equipment used in a telecommunications centre

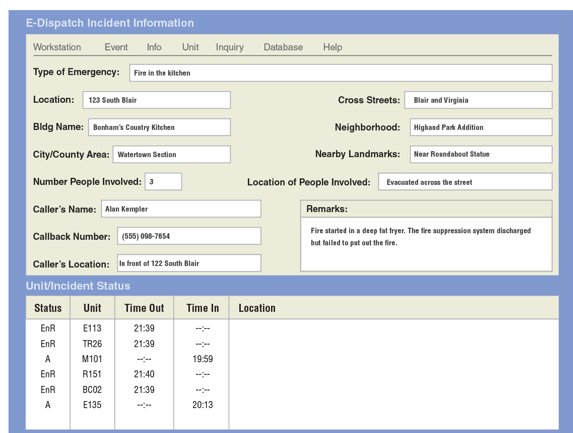

Processing Emergency Calls

Processing Emergency Calls Emergency calls must be handled quickly to ensure the safety of the community. Minimum requirements for receiving, processing, and dispatching emergency responders are included in NFPA 1221, Standard for the Installation, Maintenance, and Use of Emergency Services Communications Systems. Tele-communicators also referred to as dispatchers, are trained to obtain the correct information quickly and accurately. When the public contacts the fire station directly regarding an emergency, there must be procedures and methods in place to relay the information from the caller to firefighters accurately.

Collecting Information Based on local protocol, the information that should be gathered includes:

- The type of emergency

- The location of the emergency:

- Cross street(s)

- Building name

- Neighborhood

- Area of city/county

- Nearby landmarks

- The number and location of people involved

- The name and location of the caller

- The caller’s callback number

**NOTE: Provide life safety directions if the caller is at immediate risk. **

Relaying Information to Responding Units or Personnel

Once an emergency has been reported, the information must be transmitted to the responding units or personnel. The more time that it takes for receiving, processing, and dispatching units, the greater the potential for severity of damage and injuries. Dispatch begins with some form of alert to the stations, apparatus, or individuals. Alarm notification may be one or a combination of the following:

- Visual such as station lights

- Audible

- Vocal alarm

- Station bell or gong

- Sirens

- Whistles or air horns

- Electronic

- Computer terminal screen with alarm or line printer

- Direct telephone connection with telecommunications center

- Radio with tone alert

- Scrolling message boards

- Television override

- Radio

- Pagers

- Cellular telephones

- Smartphones

- Home electronic monitors

- Landline telephones

- Mobile Data Terminal (MDT)

|

A type of pager that volunteer fire departments use. Fire departments may use pagers to alert members of an emergency. Each pager or group of pagers can be set to a specific frequency. Dispatch can send alert codes to these specific frequencies. When the pager receives its codes, it alerts the wearer by tone, light, and/or vibration. The pager will then either relay a voice message or display an alphanumeric message sent to it. When different departments or public safety agencies share the same dispatch frequency, it is desirable to set pagers to the alert setting to avoid hearing unwanted radio traffic. |

|

| Sirens, whistles, and air horns are mostly employed in small communities and industrial facilities.The alerting device is mounted on a water tower, radio tower, or top of a tall building. These devices produce a signal that everyone in the community can hear. Civilians will be aware that emergency traffic may be on the streets; however, some may also be inclined to follow the apparatus and congest the emergency scene. |

|

Information regarding the emergency must also be broadcast to department members using an established means of communication located in the station or apparatus. The broadcast should include information received from the caller and information from the pre-incident plan developed for the specific address or facility. Basic information to be broadcast generally includes:

- Units assigned

- Type of emergency

- Address or location

- Dispatch time

- Current conditions, such as wind direction/speed and road closures

- Units substituted into the normal assignment

**NOTE: Firefighters may be able to review pre-incident information in the apparatus during response.**

Lesson 3

Outcomes:

- Describe radio equipment and procedures used for internal fire department communications.

- Handle emergency and nonemergency phone calls.

- Use a portable radio for routine and emergency traffic.

Radio Communications

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates all radio communication in the United States. The FCC issues radio licenses to fire departments that operate radio equipment. Depending on the radio system in a particular locality, one license may cover several departments that operate a joint system. Local department rules should specify who is authorized to transmit on the radio. It is a federal offense to send personal or other unauthorized messages over a designated fire department radio channel.

** NOTE: Business and Industry Canada regulates radio communications in Canada. **

Radio communication is essential to safe and efficient emergency scene operations. Most fire departments use clear text, using plain English rather than agency specific codes such as 10-codes. Standardized emergency-specific words and phrases are included within clear text.

Fire department radio systems are used to communicate the following:

- Alert units of an emergency

- Coordinate tactics at the emergency

- Request additional resources

- Monitor the activities of units and individuals

In many departments, all facilities, apparatus, official vehicles, and personnel are assigned radios during emergencies or on a daily basis. Personnel are trained in local radio procedures including periodic radio tests, and both emergency and nonemergency radio operations.

Internal communications require you to have general knowledge of:

- Radio systems and how they work

- Limitations of radio communications

- Fixed, mobile, and portable radios assigned to you

Radio Systems

The radio systems used in the fire service can be classified according to their location and size. Radio systems also have various signal transmission options. All radio systems feature several transmission channels that can be assigned to emergency or nonemergency traffic.

Location and Size

Radios used in fixed locations such as fire stations, telecommunications centres, training centres, or administrative offices are referred to as base station radios (Figure 2.7).

Understanding Base Stations

Key Features:

- High-Performance Equipment

- Base stations boast robust transmitters and receivers that are less prone to interference compared to mobile or portable radios.

- Core Components

- These stations are equipped with essential components like a receiver, transmitter, antenna, microphone, and speakers.

- Reliable Power Source

- They run on the building’s electrical system and are backed up by an emergency generator to ensure functionality during power outages.

- Integrated Systems

- Often, base stations are linked to the fire station’s alarm notification system for enhanced coordination and response.

- Mobile radios (Figure 2.8)

These are mounted in fire apparatus, ambulances, and staff vehicles and are powered by the vehicle’s electrical system.

**NOTE: Base stations are crucial for effective communication in emergency situations. **

Understanding Mobile Radios

Setup:

Installed in Vehicles: Mounted in fire apparatus, ambulances, and staff vehicles.

Vehicle-Powered: Operates on the vehicle’s electrical system.

Features:

Accessible Controls: Receiver and transmitter within easy reach in the vehicle cab.

Headset Connectivity: Available for all riding positions; additional connections on pump and aerial apparatus.

External Antenna: Enhances signal reception.

Performance:

Superior to portable radios but not as powerful as base stations.

**NOTE: Mobile radios are key for effective communication in vehicles during firefighting operations.**

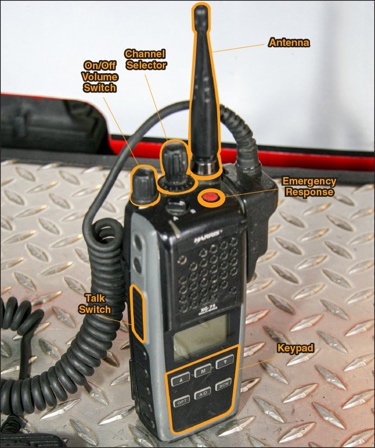

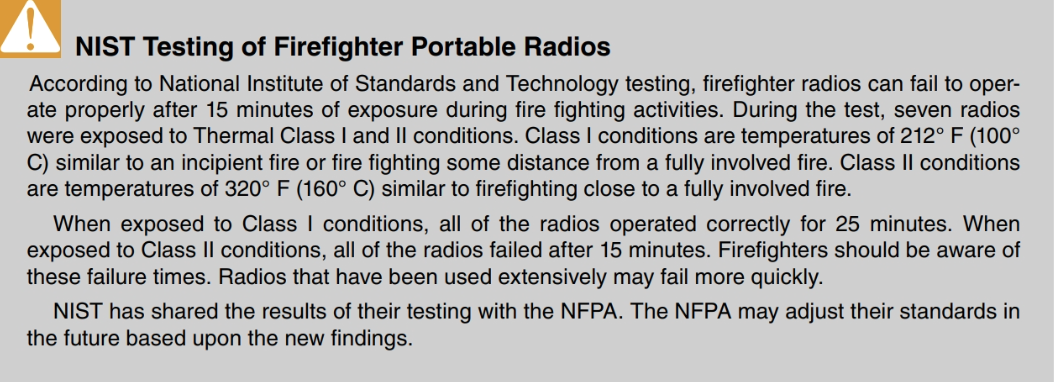

On the other hand, portable radios (Figure 2.9) are handheld devices that are less powerful than fixed or mobile radios.

Understanding Portable Radios

Power & Portability:

- Handheld and less powerful than fixed/mobile units.

- Operated by rechargeable/replaceable batteries with chargers at fire stations.

Usage & Safety:

- Can fail in harsh fire-ground conditions.

- Must be intrinsically safe in hazardous environments.

Distribution:Varies by department protocol, from officers only to every team member.

Features (Figure2.8):

- External antenna on top.

- Controls include channel selection, volume adjustment, and push-to-talk.

- May have an emergency button and a telephone-like keypad.

**NOTE: Portable radios are important for on-the-ground communication but have limitations.**

Signal Transmission

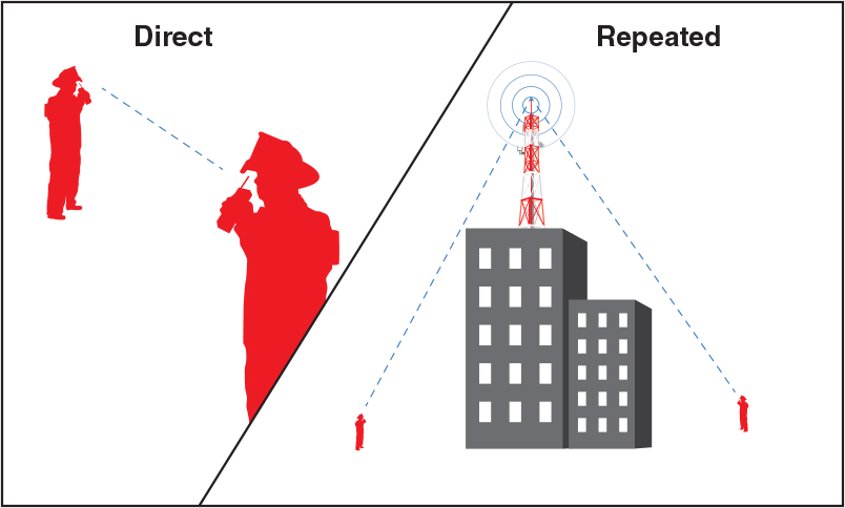

Direct communication (Figure 2.11)

Refers to the straight-line travel of radio signals between the transmitting radio and the receiving radio. This allows multiple groups to use the same channel over distances. A user simply presses the talk button to respond.

Repeaters (Figure 2.11)

May be used to boost signals for greater distance or system capacity. Due to the potential for high user volume, there might be a brief wait—signalled by a tone—before the radio is ready for speaking.

Fireground Channels

Enable modern fire and emergency services to communicate across multiple radio frequencies. Typically, there’s a dedicated dispatch channel, and when units arrive at the incident a Command channel is assigned to the Incident Commander (IC) and a separate tactical channel for fireground operations. As incidents escalate, additional channels accommodate the growing complexity and the involvement of other agencies.

Nonemergency Channels

Are used in some departments for the training center, code enforcement, and administrative personnel. The use of these channels is regulated by the AHJ.

Radio Limitations

As the fire service has increased its dependency on portable radios, limitations to their use have become more apparent.

What do you think are some limitations that may impact internal communications?

The main limitations or barriers to all radio transmissions include (Figure 2.12):

- Distance

- Physical barriers

- Deadzones

- Interference

- Ambient noise

Distance

The distance the signal will travel is determined by the power of the transmitter and receiver, as well as the height of their antennas. Using repeaters can extend this range. If you encounter static or broken messages, it usually means you’re nearing the limit of the signal’s reach.

Physical Barriers

Any physical barrier between the transmitter and the receiver can block the signal. The signal may be completely blocked, partially blocked, or reflected. Firefighters in tunnels, basements, or buildings may use the talk-around function for local communication but might struggle to reach the Incident Commander (IC) or telecom center. Your own body can also interfere with the signal; adjusting your position 90 degrees or holding the radio higher and the antenna vertically can help overcome these barriers.

Dead Zones

Dead zones are remote areas or locations inside structures that cause the loss of cell phone or radio signals. To lessen this, repeaters might be installed in some buildings. Improving reception could be as simple as moving closer to external features like walls, roofs, windows, or doorways. Fire inspectors and personnel should perform radio checks during preincident planning to verify that radios can be used in all areas of the building. In large metal and concrete structures, where radios may fail, alternative communication methods like runners might be necessary, although direct communication may still be possible within the dead zones.

Interference

Manufacturers design high-quality transmitters, receivers, and repeater systems to filter out interference.

Interference can originate from various sources. Sources of interference may include but are not limited to:

- Another powerful radio signal

- Vehicle ignitions

- Electric motors

- Computers

- Cellular telephone towers or transmitters

- High-voltage transmission lines

- Equipment that contains microprocessors

- High-power radio sites such as television and radio stations

** NOTE: The fire department administration or AHJ should specify and purchase the best quality radio systems that are available within the resources they have. **

Ambient Noise

Emergency scenes are filled with ambient noise that can make radio communications difficult. New technology has developed noise-cancelling microphones that may help. Each mobile or portable radio operator is responsible for overcoming ambient noise at a scene. The following are some ways to overcome ambient noise:

- Turn off apparatus audible warning devices when they are no longer needed.

- Move away from noise-emitting equipment when transmitting.

- Follow radio procedures at all times.

- Move to a location that blocks wind noise.

- Use your body or PPE to create a wind barrier when transmitting

Radio Procedures

Local SOP/SOGs will dictate a specific radio channel that is available to all units and personnel at the scene, the telecommunications center, and in some cases, other fire department facilities and the public. Therefore, it is important to follow local protocol for sending a message. Depending on the local radio system and protocols, frequencies may be monitored. All recorded transmissions become part of the official record on the incident and may be made public under open records laws or Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

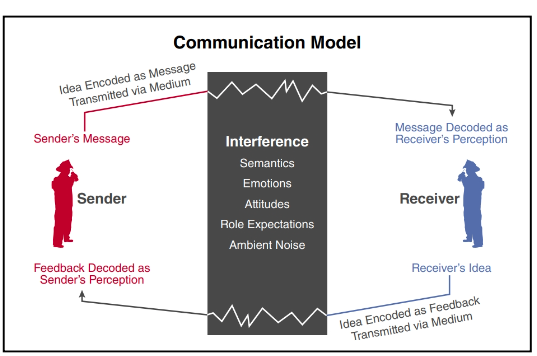

Everyone at the emergency scene should follow two basic communication rules:

- units or individuals must identify themselves in every transmission as outlined in the local radio protocols.

- The receiver should acknowledge the message.

- Requiring the receiver to acknowledge every message ensures that the message was received and understood.

- This feedback can also tell the sender if the message was not correctly understood, and further clarification is necessary.

**NOTE: A good practice is to key the microphone and wait a second or two for the signal to capture an antenna before starting your message. Keying the microphone and immediately speaking often results in a message being cut off at the start. **

When transmitting information and orders, adhere to the ABCs of good communications: Be Accurate, Brief, and Concise. Consider the difference between the following two radio communications:

- Radio Communication 1: This is Lieutenant Thompson on Engine 57. I need another truck company at this location, 1400 South Memorial, for additional personnel.

- Radio Communication 2: Engine 57 to Dispatch — assign one truck company to 1400 South Memorial.

The second example is accurate, brief, and concise.

Experience at emergency incidents has shown that background noise and personal protective equipment can significantly affect the ability to hear and understand radio transmissions.

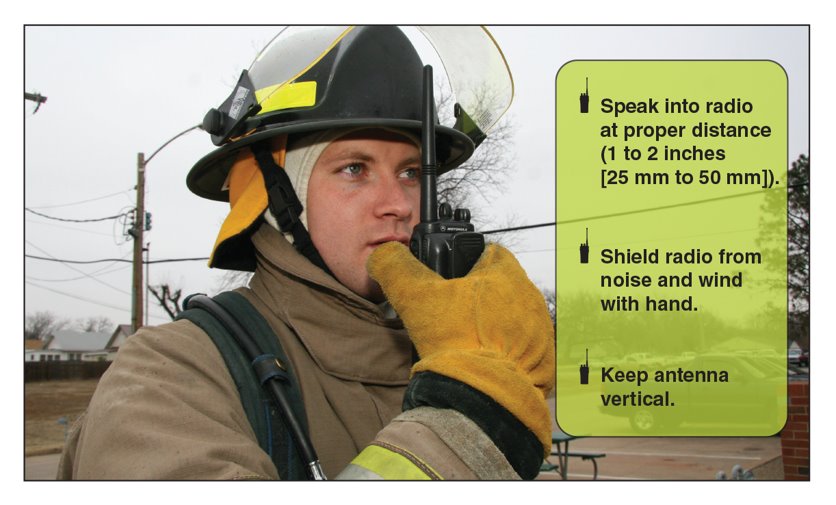

To improve your ability to hear and be heard, you should follow these radio communications best practices (figure 2.12):

- Plan your message before speaking into the microphone.

- Speak clearly at a moderate pace without fillers like “ah” or “um.”

- Use appropriate emphasis and maintain a steady tone without shouting.

- Pronounce words correctly and maintain a moderate voice volume.

- Conclude comments decisively and keep your pitch even.

- Avoid slang, eating, or chewing gum while speaking.

- Ensure clarity and brevity in your communication.

- Wait for a clear frequency before transmitting, giving priority to emergencies.

- Keep language professional and the microphone close to your mouth.

- Speak directly into the microphone and use it as recommended by the manufacturer.

- Confirm receipt and understanding of messages by repeating them.

- Protect the microphone from noise and environmental elements.

- Keep the radio away from noise sources and avoid accidental transmission activation.

- Maintain a vertical antenna position for optimal signal transmission.

- Place the microphone against your throat if you cannot be understood through your SCBA facepiece. Do not remove your facepiece to talk into the microphone.

- Practice communicating with your portable radio while wearing your SCBA before you use it in an emergency.

![]()